|

|

ALAIN

SAINT-SAËNS

Corresponding Member

of the Academy of Letters,

Bahia, Brazil

|

|

Front Cover Art Design:

ANA

MARÍA CALATAYUD |

ISBN: 978-1-937030-56-8 |

|

|

'I have known Professor Tracy K. Lewis

for years. We have translated some same novels or books of poetry in

different languages. He is an excellent translator and a sound literary critic.

Furthermore, Professor Lewis is also a distinguished and renowned poet in three languages

(English; Spanish; and Guarani, the Paraguayan native language). I

deeply admire his wonderful poetry. Nobody better

than great American poet Tracy K. Lewis could have translated my poems with such a

noble heart and a divine touch of grace.'

Alain Saint-Saëns

|

|

ALAIN SAINT-SAËNS

DEDICATING COPIES OF

INFANCIAS BAJO LOS

LAPACHOS

AT THE ALLIANCE

FRANÇAISE

IN ASUNCION, PARAGUAY

DURING AN EVENT

SPONSORED BY

THE SWISS AMBASSY,

MARCH, 18, 2014. |

|

|

|

|

|

RENÉE FERRER, THEN

PRESIDENT

OF THE PARAGUAYAN ACADEMY

WITH ALAIN SAINT-SAËNS,

MARCH 18, 2014. |

ALAIN SAINT-SAËNS WITH

ALEJANDRO GATTI, CRITERIO EDICIONES EDITOR. |

|

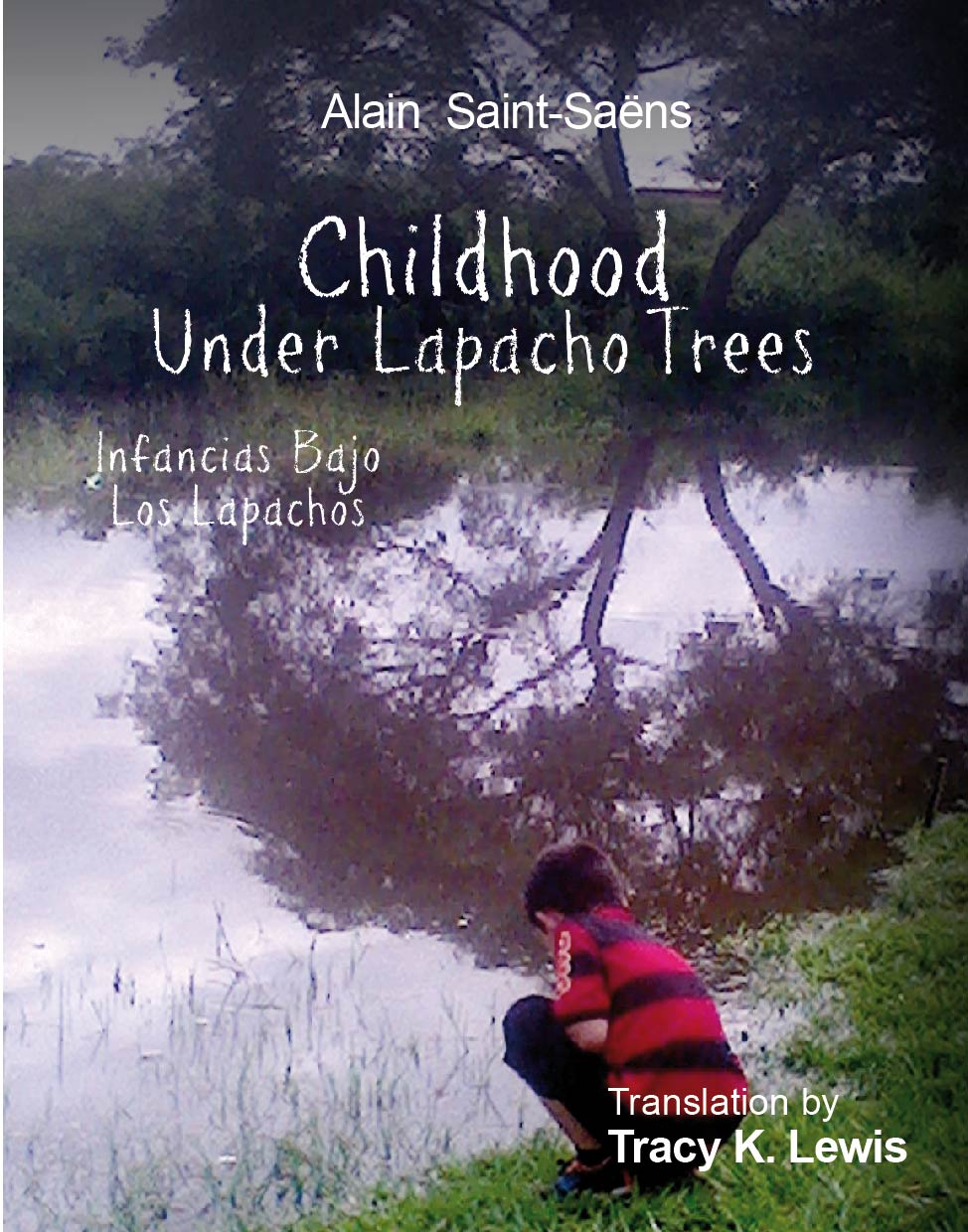

Translated from French and Spanish

First Edition

by American Poet

TRACY K. LEWIS

State University of New

York at Oswego, USA |

|

|

'Alain Saint-Saëns paints a dolorous picture of abused

children in this text, one which rings with truth and

poetically saves them from obscurity. This poet's

critique of the adults is savvy and relentless, while

these figures remain a force of power and desire that

weaves a web of helplessness around the vulnerable under

their control. The crimes are treated in a skillful way,

eliciting double meanings, as in "father/Father".

Alain Saint-Saëns'

images from Paraguay certainly resonate with scenes in

so many cities around the world, including Chicago.

The translation aptly conveys the spirit of the original

without restraining itself to a literal rendering.'

CYNTHIA T. HAHN,

Poet and Professor of Romance Languages,

Lake Forest College, IL (USA)

|

|

|

|

LUNA NARANJA

Luna

naranja, noche mágica,

Luminosidad onírica,

Todo duerme, tiempo suspendido.

Furtiva y silenciosa,

La anaconda curiosa

Digiere un perro perdido.

Del verraco huraño

El deseo de la cerda

Arruina el sueño.

Ofendiendo la mirada,

El gordo sapo azorado

Osa un mohín lánguido.

Zinedín, mi niño,

Triunfando sale de un sueño,

Todo mojado de sudor.

Un gallo, en lo alejado,

Sobre sus espolones alzado,

Saluda el pálido resplandor.

|

ORANGE MOON

Orange

moon, wizard night,

Light of dream,

All’s asleep in pause of time.

Noiseless furtive anaconda

Darkly browsing

Casually digests an errant dog.

Lust for she-pig

Trumps the churlish boar’s

Intended sleep,

While wounding sight

A toad leers fatly

In its sluggish fright.

Zinédine my child

Exits sleep triumphant

Steeped in sweat,

And somewhere else, a rooster

Rises on his spurs

To crow the inchoate sun.

|

|

SOLDADITOS DE PLOMO

Acosta

Ñu, lugares malditos,

Tres mil quinientos soldaditos,

Hijos de Paraguay tan valiosos

Contra bárbaros odiosos

Lucharon como hombres,

Cayeron gentilhombres.

¡Qué nadie sobreviva al día!

¡Qué se mueran todos, sin misericordia!

El verdugo brasileño bajó los ojos

Cuando madres paraguayas gloriosas,

En los brazos sus sangrantes hijos,

Quemaron orgullosas y silenciosas.

De Brasil no hubo descargo,

El tiempo no trajo olvido.

A veces el viento sopla tanto

Que se escucha como un llanto.

Agosto dieciséis, sin embargo,

Regala el soldadito el oído.

|

LITTLE TIN SOLDIERS

Evil

battlefield, Acosta Ñu,

Three-thousand and a half of children,

Gallant sons of Paraguay it threw;

Against barbarity

Of full-grown men

They fell in manhood premature.

No quarter, kill them all!

Let your mercy die along with them!

So saying, gazed with sunken eye upon the pyre

The butcher from Brazil,

While Paraguayan mothers, brave and silent

Fed their children’s corpses to the fire.

No regrets came ever from Brazil,

No closure where the children bled,

No sound but dirges of the miming wind

Recalling spasms of the dead.

16 August, slaughter of the soldier-waifs

Who now in memory at least, are safe.

|

|

TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE

I’m doubtless not the first in pointing out

the fortuitous resemblance between the Spanish words traducción (translation) and

traición (betrayal),

nor in bringing to light what the second term reveals about

the first. Far from fostering a slavish copy of the

original, what the translator of literary texts does is to

alter them, to subvert them, and finally to “betray” them.

Beyond simply re-painting a house, the translator’s task is

to re-construct it with a new floor plan and a new

architectural style.

What’s more, this reconstruction is involuntary and

unavoidable; we are forced to betray the original

because replacing one language with another necessarily

means replacing the very materials of which the text is

made. Not even the simplest, most direct

substitutions—“tree” for “árbol” for example—can be exact

equivalences, since each word differs from the other in

spelling, in sound, in rhythm, and in the connotational aura

which surrounds it.

For Paraguayans, “árbol” is a subtropical

construct, exuberant with fruit and greenery, shadowed

perhaps with the Guarani sounds of ka’i and urutau,

whereas North Americans might visualize “tree” in the

magnificent garments of autumn, or in the melancholy

nakedness of winter. And if this is so for individual

words, what can we say of sentences, paragraphs, poems, or

entire novels?

When Alain Saint-Saëns invited me to translate

his book of poems Enfances, therefore, he was

actually inviting me to transform it into something else.

Complicating matters was the fact that Alain gave me his

text in two languages, French and Spanish, and I had

to consider both versions in producing mine. For that

reason, I am a traitor twice over to the same piece of

literature!

The paradox of the translator’s craft, however, is

that his or her “betrayal” occurs in a context of the most

sublime faithfulness: I transform the text while respecting

it profoundly, I transform the text precisely because I

believe it deserves an analogous presence in my own

linguistic universe. Saint-Saëns’ poems express a vision

eminently worthy of expression in any latitude, a vision

which justifies the hard work of seeking its correspondent

language, however inexact, in my own small corner of the

English-speaking world. I thank Alain for the chance to

re-create his text in English and in so doing to complete a

triangle that joins three languages, three countries, and

one entire world of beauty, anguish, and deeply-felt human

emotion.

Tracy K. Lewis

|

|

|

|

Poems That Hurt

Childhood Under Lapacho Trees by Alain

Saint-Saëns is composed of sixteen poems that

hurt. The little kid who on a rainy day,

camouflaged by the storm, is crushed like a

caterpillar on the sidewalk, who is to cry for

him? Nobody. The poet does not say it. He

just cries for the poor child in his poem.

Squashed undesired bug,

Street child by the roadway, dead.

And the little

girl who is begging by day and sexually abused

by her father by night, as she lives a dreadful

secret purgatory, the end of which can only be

desired death? She hurts too.

Won’t the same happen, predicts the poet, to the

innocent girl who stole a cup of milk from his

window, and who, without any doubt in his mind,

will be raped and gotten pregnant by some

drunk? Will her youth not be cut off almost

overnight, turning her into a poor single mom

with a child who will likewise be trapped in the

same endless nightmare and the same cycle of

poverty?

Who then in satyr’s mirth of alcohol

Will mount her on a drunken cross

To break her back of youth?

Hope, however,

emerges with Natí, who will be able to go to

school. Education, for the poet-teacher

Saint-Saëns, is the way out for such as Natí, as

it would be for the young girl impregnated by

the village priest,

Saw her faith un-grounded,

Her nubile belly stroked and rounded.

It also hurts

when the poet focuses on his own son and watches

over his sleep. In a pair of poems, we watch

over Zinedín’s bed along with his father under

an orange tree, or look at the babysitter who as

in a Renaissance painting sleeps peacefully with

the boy on her shoulder, while he dreams of the

Three Wise Men. The child’s naïve imagination

is beautifully drawn in another poem, in which

the poet describes his child inserting a

dinosaur toy in the family manger. In yet

another poem, the poet, dazzled by the Brazilian

city of Vitoria, hopes to go back there one day

to see his son frolic in the waves:

He sees and waves again

Will crowd upon the shore.

Innocence,

dreams, water, toys, mother and father: these

are in contrast to the naked reality of the

lives of street boys, or that of Jesús, the

quadriplegic child with AIDS:

Fouled blood his only crime,

He sees not, nor hears,

But only these eleven years

Awaits in comfort of his faith

Some gesture of his God.

And that is what hurts. Zinedín, the poet’s

little son, will one day have to face the crude

reality of his country, which like the curious

anaconda digesting a stray dog in one of the

poems, eats up and eradicates faith and the hope

of a better world. Life in the streets is a

cruel universe for the children with whom

Zinedín will live, and the poet’s hope is that

his son can transcend the reality around him.

That is why the poet tells us his son paints,

paints the future:

His world of forms

And colors elsewhere made,…

What pale of day first breaks

When man becomes not

Flesh but something more?

With that

painting, he changes and transforms his world,

and that of all children, including the horrid

world of the street kids. That is why the poet

says that the painter, 'de simple mortal,' is

transmuted into an 'arcángel.' Emerging from

dirty water, horror, incest and rape, the street

children bear within their little tortured

bodies a genuine, pure and sparkling soul. From

mere mortals they can become archangels through

the magic touch of a dreamer.

These poems hurt, but more than that they call

us to reflect on what kind of society we live

in, and what model we are building for

forthcoming generations. There is a social

concern in this book that renders it into a

devastating critique against a society that

creates and reproduces countless abused

children. Paraguay, a culture that revels in

loud parties and the giving of presents,

celebrates Children’s Day. That, however, is

also the anniversary date of the cruel slaughter

of some thirty-five hundred child soldiers by

Brazilian troops at the Battle of Acosta Ñu

during the War of the Triple Alliance. Alain

Saint-Saëns, the poet of suffering children,

invites us in a final poem to question the way

we teach our own history:

Evil

battlefield, Acosta Ñu,

Three-thousand and a half of children,

Gallant sons of Paraguay it threw;

Against barbarity

Of full-grown men

They fell in manhood premature.

I

pray these poems, a real mirror of a wounded and

suffering Paraguayan society, will find their

reflection in the hearts of the men and women

who read them, and help thereby to solve the

problems they courageously denounce. Freedom

and justice are not a given; they must be built

and re-built every day.

Leni Pane

Paraguayan Academy of Spanish Language

|

|

Alain Saint-Saëns is a Corresponding Member

of the Academy of Letters, Bahia, Brazil |

Alain Saint-Saëns is a

poet, a playwright,

a novelist, a literary critic, and a translator. He recently

published three major academic

studies,

Luis

Ruffinelli, eximio teatralizador, 1889-1973

(2018);

El trébol

de cuatro hojas. Poetas paraguayos (2017); and,

Paladin de la liberté. Juan Manuel Marcos poète

(French version, 2015; Spanish version, 2017).

His books of poetry are:

Cantos paraguayos. Poemas de libertad

(2009);

France, terre lointaine. Poèmes de l'errance

(2011); Curuguaty. Poema lírico (2012); Infancias

bajos los lapachos (2014);

El Banquete de Tonatiuh. Poema lírico

(2015);

Un coin de France. Le Lycée International Marcel

Pagnol (2016); A Bahia de

todas as gaivotas (2018).

As a playwright, he recently

authored, The Wagon (2018);

Artigas (2017);

Soledad. Vida y

muerte de una poeta (2016);

Romeo y Julieta en

el Marzo Paraguayo (2016); The Jump (2015);

Pecados de mi pueblo

(2013); and,

Ordeal at the Superdome (2010).

Ña Celestina. Asunción madre indigna (forthcoming in

2018).

His published novels are

Hijos de la Patria (2015); and

Dos viudas y un huracán

(2016).

He translated recently from Spanish to French,

L'hiver de Gunter by Juan

Manuel Marcos (2011);

Ignominies. Poèmes et Psaumes by Renée Ferrer (2017);

Cupidité by Maribel Barreto (2018);

and Poésie Complète by Rubén Bareiro Saguier (forthcoming,

2019); from Portuguese to

Spanish,

Un río en

los ojos, by Aleilton Fonseca (2013); from Portuguese to

French, Sesmarie, by Myriam Fraga (forthcoming,

2019); from English to

French,

Loin, très loin de la maison de ma mère

by Barbara Mujica (2005); and from French to Spanish,

El hombre de

todos los silencios, by Ezza Agha Malak (forthcoming, 2019).

|